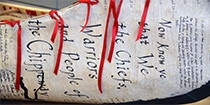

Treaty Canoe (1999, 12’x24”x32”), built much like a birch bark canoe, is a performance/sculpture/installation that is made from red and white cedar, red-ribbon, glue, and a papier-mâché of treaties replacing the ‘bark-skin’.

Using dip-pen and ink, treaties were ‘transcribed’ performatively by many hands from machine-printed text onto hand-made linen paper to create facsimile documents. In a de-colonizing gesture volunteer ‘scribes’, most of whom had never read a treaty before, undertook a close reading and transcription before reluctantly and poignantly signing the contracts in the stead of their original faithful negotiators.

Invariably these ‘scribes’ choose to transcribe a treaty from where their ancestors originally settled, where they themselves were born, or where they live now, thus learning whose traditional territory (much un-ceded) they occupy. The scribes also begin to question the fairness of the treaty, reflecting on the conditions under which it was negotiated, the cross-cultural differences in languages and understanding of terms (even the term ‘treaty’ itself), the disparity between oral and textual authority and concepts of land and property, not to mention the issue of whether the terms of the treaty as printed have actually been enacted.

The canoe, an example of Indigenous technology, is a national cultural icon. Our cultural myth asserts that through paddling the canoe we can have an unmediated experience of wild ‘nature’ and by becoming part of nature, ‘Indigenize’ ourselves, becoming more fully Canadian in turn. Ironically this is done without the majority of Canadians being engaged in any sort of positive relationship with Indigenous people, and with no understanding that they are on someone else’s traditional territory, or in someone else’s sovereign nation.

Marrying treaties to a canoe is an attempt to decolonize the canoe: to question the cultural myths and to point to a relationship where parties treat with honour, as equals, allies, and trading partners, reaching agreements to share the land, resources, and the wealth flowing from them to the mutual benefit of all signatories.

Treaty Canoe is, of course, text. Its sister piece, the megaphone Treaty of Niagara 1764, (birch bark, copper wire, red paint, about 24 x 12 inches, 1999) is all but mute. The Treaty of Niagara, which affirmed Indigenous sovereignty, was negotiated with at least 24 Indigenous nations present following The Royal Proclamation of 1763.

Treaty of Niagara 1764 was inspired in part by Rebecca Bellmore’s performative work Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother, print historian D.F. Mackenzie’s work on The Treaty of Waitangi entitled The Sociology of Text: Oral Culture, Literacy, and Print in Early New Zealand and John Borrows’ Wampum at Niagara. These two scholarly works address the authority of oral tradition in law and reveal that Indigenous sovereignty was never relinquished, while Bellmore’s work asserts the authority of Indigenous voice in the flesh, in the spirit, on the land, in the here and now. Unable to speak for Indigenous people, I humbly offer this simple tool, so I can stand aside, and listen.

Also in the installation are a Two Row flag, referencing the Two Row Treaty, depicting two canoes traveling down the same river, each steering its own course, and an HBC point blanket, evoking the corporate foundations of Canada and the historic economic ties between Indigenous nations and Settlers.

The presence of The Treaty of Niagara 1764 as a symbol of Indigenous sovereignty is paramount to understanding Treaty Canoe. Treaty Canoe is a Settler canoe, addressing the Settler problem: that we see the world through the ideology of the colonial lens. Treaties are not ‘bills of sale’, but the basis of an ongoing relationship and continual negotiation for the mutual benefit of all parties. They are the founding documents of what is still a poorly-defined country, and make clear that We are all Treaty People.

Alex McKay 2016

treatycanoe.ca